Incredible Journeys – Bird Migration Explained

While many species of bird make the UK their home all year round, some just visit for the summer or winter months and then head off to distance shores for the rest of the year.

In fact, lots of species fly thousands of miles during their annual travels, crossing whole continents without stopping to reach the mating or feeding grounds they’re heading for.

Of course, we all know this phenomenon as migration and the birds that do it migratory species.

Some are well known – many people look out for the return of Swallows in April as an early and lovely indicator of spring. But others are less well known such as the Sanderling, a small, scuttling sparrow that spends the winter here and then heads off to the Arctic to breed.

But what causes birds to take such long – and sometimes treacherous – journeys and how are they able to keep going for such extended periods of time without needing to take a break?

In this blog, we examine bird migration, taking a deep look into one of nature’s most spectacular phenomena to find out more about what makes it possible.

Why Do Birds Migrate?

Although lots of birds migrate to many different areas of the world, there are just two main reasons why they do it. They are either seeking areas to feed or areas to nest. Essentially, they are moving from an area of depleting resources to an area of abundant resources.

For example, in the spring time, birds might move north as the warmer weather brings an abundance of insects. Here they settle. But as the colder weather begins to set in again, and insect levels fall, they return south to the tropical regions where they breed.

This cycle takes place year in, year out, as the climate dictates where food will be most prevalent.

The UK sees many winter visitors due to its mild climate. Birds arrive here from the north or east in autumn and stay to the spring, whereupon they return from where they came from.

Around 50 species of bird also leave our shores to travel south over the in winter, including the aforementioned Swallows and their close cousins the Swifts, which winter in southern Africa to avoid the cold European winters.

Here they find an abundance of insects that plague the local wildlife such as hippos, buffalo and wildebeest to feed on. Swifts, in particular, face one of the longest migrations, travelling around 14,000 miles from Europe to southern Africa, passing through around 25 countries en-route.

They can fly at speeds of up to 70mph, meaning they can reach their destination in as little as four weeks, making their journey one of the most impressive in the animal kingdom.

Once the weather in southern Africa starts to cool and their winter appears on the horizon, Swifts and Swallows make a return journey to Europe, where they spend the spring and summer breeding.

When Do Birds Migrate?

As we’ve heard, birds migrate when resources such as food become depleted, so they travel to places where they are abundant. This is generally related to the weather. As the weather grows colder in a region, food such as insects become less available, marking the time when birds need to move.

Unsurprisingly, in the UK, this coincides with autumn, and this is the time when summer visitors leave Europe in the search for warmer climes in the south. Autumn in the northern hemisphere aligns with spring in the southern hemisphere, so when birds such as Swifts and Swallows arrive in southern Africa, they do so in time for late spring and summer.

Obviously, the opposite is true. Autumn in southern Africa aligns with spring in Europe, so when autumn comes and the Swifts and Swallows return to Europe, again, they are doing so in time for late spring and summer. They travel to Africa to feed and back to Europe to breed, and by doing this, they avoid wintering in either place.

How Do Birds Know Where To Go?

Bird navigation is an extremely complicated subject, and therefore is the subject of a lot of research. In simple terms, however, there are two components of bird migration and navigation at work.

First is an instinctual or innate element. Birds know instinctively in which direction they must fly during migration and they are born with this. This can be observed in juvenile birds that have never migrated before, demonstrating that instinct plays an important role.

However, research also shows that if adult birds are displaced, they can reorientate themselves and find their way back to the correct route, demonstrating there is more than just instinct at work. This is genuine navigation.

So, how do birds do this? Well, they have a variety of methods including the use of landmarks – seabirds, for example, follow the coast – the Earth’s magnetic field, the pattern of the stars, sound, barometric pressure, polarised light, and believe it or not, even smell.

All of these elements enable birds to travel distances of thousands of miles and reach precisely the destination they’re searching for, and get back again, even if they are blown off course by gale force winds, storms or other weather events.

Different Types Of Migration

Although most migrations take place for the same reason – to find new resources – there are many different types based on the direction of travel, and length, and so on. The main types of migration include:

Latitudinal

This is where birds fly from northern regions to the south, and vice versa.

Longitudinal

Migration from east to west and vice versa, which is particularly common for birds in Europe.

Irruptions

These are irregular migrations that result from a lack of food or water and often take the form of hundreds of birds suddenly deciding to move in search of these resources.

Altitudinal

This is where birds move from high ground to lower ground in the winter, ensuring they are less exposed to bad weather.

Reverse migration

Reverse migration is not a true form of migration because it involves birds, usually juveniles, becoming confused and flying in the opposite direction to that which they should be. This can often end in them getting lost.

What Birds Migrate From the UK?

So, we now know why birds migrate, how they navigate, and the different types of migration there are, but which birds are migratory and which are from the UK?

Birds that migrate to and from the UK are divided into winter visitors and summer visitors. Winter visitors arrive in the autumn from colder climbs in the north, to take advantage of what is to them the warmer weather here. Summer visitors come here in the spring for the warmer weather of our spring and summer, enabling them to breed and raise young, before returning south again.

Some of Our Most Popular and Recognisable Winter Visitors Include:

Bewick Swan

The smallest of the Swan species, the Berwick travels 2,500 miles from Siberia to winter in the UK, and are often found on farmland, freshwater wetlands, and coastal bays. An easy way to recognise them is via their distinctive yellow and black beaks.

Pink Footed Goose

Often heard before they’re seen with their loud honking, and flying in huge V-shaped skeins, Pink Footed Geese return to the UK in autumn where they can be found in coastal areas, estuaries, and on farmland in large numbers.

Black-tailed Godwit

A large wading bird, the Black-tailed Godwit travels to the UK from Iceland to spend the winter here. It uses its long legs and bill to search coastal mud for worms and snails and has distinctive black and white wing bars.

Fieldfare

A charming thrust that arrives in the UK in October from Northern Europe. They can be distinguished from other thrushes by their distinctive grey head and rump.

Popular Summer Visitors Include:

Osprey

The only raptor on our list, the magnificent Osprey winters in West Africa then migrates to the UK in the spring. It remains mainly around coastal areas where it hunts for fish.

Swallow

The classic foreteller of summer’s arrival, anyone interested in birds welcomes the return of the Swallows. Swallows travel from the eastern part of South Africa to the UK and are known as aerial acrobats, swooped on insects to catch them. They can often be found roosting in large numbers in reed beds.

Turtle Dove

The Turtle Dove is one of just a smaller number of seed eaters to migrate long distances. It comes to the UK in spring to summer on farmland here, before returning to the Sahara in the autumn.

Swift

Like the Swallow, the Swift heralds the countdown to summer. They arrive in April and May, breed here, and set off on their long journey back to Africa in August or September, prompted by the lack of insects to eat.

Of course, there are far more species of bird that migrate to and from the UK each year than we have listed here, but there are too many for us to cover.

However, we hope this article has given you an insight into the complicated and fascinating world of bird migration and if you want to learn more, there are many great books available and lots of online resources to help you find out more about the amazing journeys these wonderfully impressive migratory birds make.

Our recent posts giving advice and guidance on wild birds

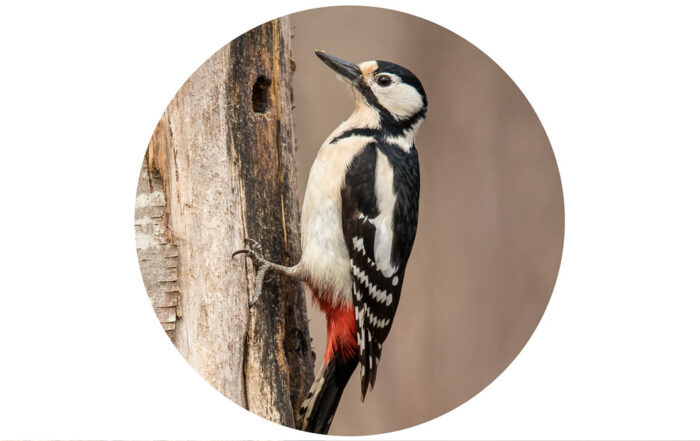

Drum Roll for the Woodpecker, One of the UK’s Best Loved Birds

Reading Time: 10 minutes One of the most intriguing and evocative sounds in British woodlands is the Woodpecker tapping on tree trunks. But is the UK home to any other varieties of Woodpecker and if so, do they drum? In this blog, we take a closer look at one of Britain’s best loved and most iconic birds and unveil the secrets of their unique behaviour.

Ground Nesting Birds

Ground Nesting Birds In an earlier article, we looked at nesting behaviour in wild birds and how you could use this knowledge to encourage birds to nest in your garden. In that article we talked about birds that nest in [...]

Incredible Journeys – Bird Migration Explained

Reading Time: 11 minutes While many species of bird make the UK their home all year round, some just visit for the summer or winter months and then head off to distance shores for the rest of the year. In this blog, we examine bird migration, taking a deep look into one of nature’s most spectacular phenomena to find out more about what makes it possible.

Leave A Comment